I haven't been able to find any Christmas stories in Ainsworth's novels (though perhaps a more assiduous scholar may be able to correct me). However, he did publish a short-lived journal entitled The Christmas Box, an annual, which ran to two editions, in 1828-9. The first was notable in that Ainsworth was able to persuade Walter Scott to contribute a ballad, The Bonnets of Bonnie Dundee, and Charles Lamb provided Verses written in the first leaf of Lucy Barton's Album. Other writers (including Theodore Hook, John Gibson Lockhart and William Maginn) furnished the remainder of the stories, and Ainsworth himself added a new tale: The Fairy and the Peach Tree.

The precocious young publisher insisted on paying Scott twenty guineas for Bonnie Dundee, which the revered author accepted with a smile, and handed over to his little granddaughter, Charlotte Lockhart.

In February, 1828, Ainsworth claimed, in a letter to his friend James Crossley: 'The Christmas Box sells admirably; we have already exceeded 2000.' The next volume, in 1829, was published by John Ebers (Ainsworth's father-in-law) and was the final appearance of this title, copies of which are now very scarce.

For more information on The Christmas Box, see S. M. Ellis, William Harrison Ainsworth and his Friends(London, John Lane, 1911), vol. 1, pp. 168-172.

Thursday, 27 December 2007

Monday, 5 November 2007

Guy Fawkes in Manchester

In Guy Fawkes (1841), Ainsworth recounts a well-known historical event, but one not normally associated with the northwest region of England. Undaunted by such details, the author sets the whole of the first book (entitled ‘The Plot’) of this three-book novel in the Manchester region, specifically placing the plotters in Ordsall Hall, just a few miles from the city centre. The hall was once the residence of the wealthy and influential Radcliffe family, and Ainsworth employs Sir William Radcliffe in a minor role, giving him a beautiful daughter Viviana, who later becomes amorously involved with the dashing Guy Fawkes. This is an anachronism, as Sir William died in 1568; Viviana, if she had existed, should have been the daughter of Sir John Radcliffe (1581-1627). Such pedantic details were of no concern to Ainsworth, who went on to introduce two other local characters into the story: Humphrey Chetham, the Manchester merchant and philanthropist (founder of Chetham’s Hospital and Library), and Dr John Dee, at that time the Warden of Manchester who is introduced as ‘divine, mathematician and astrologer, - and if report speaks truly, conjuror.’ Ainsworth’s preferred modus operandi always involved a basis of fact, usually gleaned from authentic documents (supplied by James Crossley and other antiquarians, often members of the Chetham Society). On that foundation would be constructed elaborate sub-plots and characterisations, linked to a strong, linear narrative, which the reading public found instantly accessible and appealing.

Sunday, 28 October 2007

Early literary efforts

Ainsworth was educated at Manchester Grammar School, but perhaps more importantly, came under the influence at the age of 12 (1817) of a young articled clerk in his father’s firm, named James Crossley. Five years his senior, with a formidable knowledge of Classical and English literature, Crossley had recently moved to the town from Halifax and was lodging at the Ainsworth family home.

The two soon formed a friendship, based initially on shared literary interests, which was to endure throughout their lives. As S.M. Ellis points out in his 1911 biography of Ainsworth, Crossley was: 'one who, by his wider reading and experience, could render material aid in consummating those fantasies and romantic ideas thronging in the fertile mind of the younger boy.' Although Ellis is describing a youthful relationship, the description remained accurate throughout the adult lives of the two men, with Crossley providing the research and background information to feed Ainsworth's imagination as a successful writer of historical romances.

The young Ainsworth was instrumental in organising amateur theatricals, which became part of life at King Street. A small theatre was set up in the basement of the house, and William and his school friends set about staging ambitious productions of the plays that he was already beginning to turn out with impressive speed. Most of the household became involved in one way or another, whether acting, designing and making scenery and costumes, or swelling the ranks of the audience.

Much of Ainsworth’s early work, in the form of essays, short stories and poems were signed with the name Thomas Hall (who had been a fellow schoolboy at Manchester Grammar School), and many of these were published by journals such as Blackwoods, The London Magazine and Arliss’s Pocket Magazine. The editor of this last journal was the recipient of one of the author’s youthful hoaxes. Under the name of Hall, the sixteen-year-old Ainsworth wrote to announce that he had discovered a seventeenth-century dramatist, named William Aynesworthe, introducing him(self) as follows:

'Of all the dramatic writers, one who has met with the least attention, and perhaps deserved the most, is William Aynesworthe. The chaste simplicity of his style, divested of all the ridiculous bombast which characterizes our modern writers; the elegant and rich fulness of his verse, combine to render him a writer worthy to be ranked among the first of our early dramatists.'

The writer goes on to offer specimens of six plays from the pen of his newly discovered genius, presumably resurrected from the King Street basement. Inevitably the editor spotted some anachronisms in the texts, but Ainsworth continued unabashed, offering the plays of ‘Richard Clitheroe’ to the New Monthly Magazine, with similar results. He was to use the surname Clitheroe in one of his most important novels some 30 years later, as we shall see.

The two soon formed a friendship, based initially on shared literary interests, which was to endure throughout their lives. As S.M. Ellis points out in his 1911 biography of Ainsworth, Crossley was: 'one who, by his wider reading and experience, could render material aid in consummating those fantasies and romantic ideas thronging in the fertile mind of the younger boy.' Although Ellis is describing a youthful relationship, the description remained accurate throughout the adult lives of the two men, with Crossley providing the research and background information to feed Ainsworth's imagination as a successful writer of historical romances.

The young Ainsworth was instrumental in organising amateur theatricals, which became part of life at King Street. A small theatre was set up in the basement of the house, and William and his school friends set about staging ambitious productions of the plays that he was already beginning to turn out with impressive speed. Most of the household became involved in one way or another, whether acting, designing and making scenery and costumes, or swelling the ranks of the audience.

Much of Ainsworth’s early work, in the form of essays, short stories and poems were signed with the name Thomas Hall (who had been a fellow schoolboy at Manchester Grammar School), and many of these were published by journals such as Blackwoods, The London Magazine and Arliss’s Pocket Magazine. The editor of this last journal was the recipient of one of the author’s youthful hoaxes. Under the name of Hall, the sixteen-year-old Ainsworth wrote to announce that he had discovered a seventeenth-century dramatist, named William Aynesworthe, introducing him(self) as follows:

'Of all the dramatic writers, one who has met with the least attention, and perhaps deserved the most, is William Aynesworthe. The chaste simplicity of his style, divested of all the ridiculous bombast which characterizes our modern writers; the elegant and rich fulness of his verse, combine to render him a writer worthy to be ranked among the first of our early dramatists.'

The writer goes on to offer specimens of six plays from the pen of his newly discovered genius, presumably resurrected from the King Street basement. Inevitably the editor spotted some anachronisms in the texts, but Ainsworth continued unabashed, offering the plays of ‘Richard Clitheroe’ to the New Monthly Magazine, with similar results. He was to use the surname Clitheroe in one of his most important novels some 30 years later, as we shall see.

Sunday, 16 September 2007

So who was Ainsworth?

The novels of William Harrison Ainsworth are unfamiliar to the majority of readers who enjoy nineteenth century literature today. Yet Ainsworth enjoyed a spectacular success in his own time. The son of a Manchester solicitor, he found the glittering prizes of fame and fortune in the Capital at the age of only thirty. But when fashionable London’s ardour cooled, it was his native city that provided him with the ultimate honour and recognition. But, in the course of the 122 years since his death, his works have fallen almost completely from the favour of the reading public. Up until the 1940s and 50s the better known titles were available in pocket editions, published by Everyman and similar presses, but nowadays, Ainsworth’s novels are difficult to find. A few are printed in limited quantities by local publishers, and others are available as special ‘print on demand’ items obtainable through the Internet, but the majority of the forty titles in the Ainsworth canon are only to be found in remote corners of second hand bookshops. This situation requires some explanation; so, let us take a closer look at the remarkable story of Ainsworth’s life and work, beginning with his family background in the latter part of the eighteenth century.

William’s father, Thomas Ainsworth, was a descendant of the Ainsworths of Tottington, near Bury, about 2 miles from the village of Ainsworth (the original Ainsworths of Ainsworth had died out shortly after the Civil War). He was born in Rostherne, Cheshire, in 1778, but spent his adult life in Manchester, where he was a partner in the successful legal practice of Halstead and Ainsworth in Essex Street. In the course of his professional life, he was involved with many of the public improvements in the city most notably the radical remodelling of the Market Street area. The author’s middle name was provided by Ann Harrison, who was born in Kirkham in the same year as Thomas Ainsworth. Ann was the daughter of the Rev. Ralph Harrison (1748-1810), who had been minister of the Cross Street Chapel since 1771 and became professor of Greek, Latin and ‘polite literature’ at the newly established Manchester Academy in 1786. The academy moved to Oxford in 1889, and was henceforth known as Manchester College, where there is a memorial window by Burne-Jones in memory of the Rev. Harrison. He also found time to take an interest in business matters, particularly concerning the growth of Manchester, and made a small fortune through property speculation. In this he may well have come into contact with Thomas Ainsworth, and it is quite possible that Thomas might have met Harrison’s daughter through this business relationship.

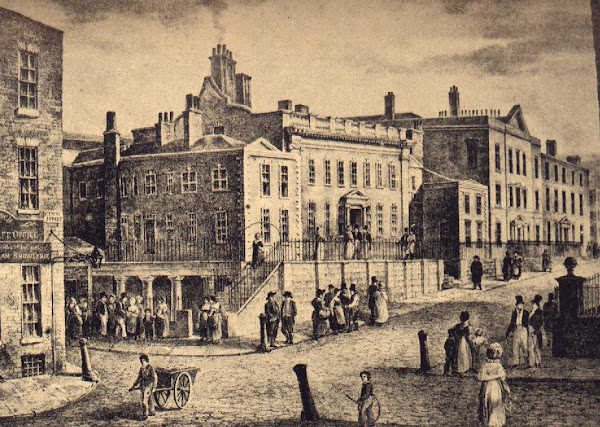

Thomas Ainsworth married Ann Harrison in 1802, and the couple established their home in King Street, at that time a prestigious residential address, in central Manchester(see illustration below). They had two sons: William Harrison Ainsworth (b.1805), and Thomas Gilbert Ainsworth (b.1806), who won a scholarship to Cambridge, but there suffered what was described as ‘brain fever,’ which left him mentally impaired until his death at the age of 70. The Ainsworths also owned a country residence, named Beech Hill, in Smedley Lane, Cheetham Hill (see illustration above), which Thomas purchased in 1811. This location was described as: ‘charmingly situated on high ground, and only a distant glimpse of Manchester was presented across the intervening gardens and fields. From the back of the house a really beautiful view extended over Crumpsall and Heaton Park – a rich well-wooded country of undulating hills.’ Here it was that the family spent many of their summer months when the boys were young. A subsequent occupant was John Edward Taylor, the founder of the Manchester Guardian, who died there in 1844. During the twentieth century, the house became a Church Army Labour Home, and was eventually demolished. There now stands a modern building; a nursing home, which retains the name of Beech Hill, but sadly without the rural aspect.

More to follow soon ...

Thursday, 6 September 2007

Ainsworth on TV!

Channel 5 screened a documentary on Tuesday 4th September, entitled The Real Dick Turpin: Revealed, featuring the historian Professor James Sharpe, of York University, who is an expert on Turpin. The programme acknowledged Ainsworth as the principal creator of the Turpin legend, in particular the 'Ride to York', and showed this portrait of the author by R. J. Lane.

Sunday, 26 August 2007

The Legend of the Lime-Tree (and the fate of the Rookwoods)

In olden days, the legend says, as grim Sir Ranulph view'd

A wretched hag her footsteps drag beneath his lordly wood,

His bloodhounds twain he called amain, and straightway gave her chase;

Was never seen in forest green, so fierce, so fleet a race!

With eyes of flame to Ranulph came each red and ruthless hound,

While mangl'd, torn - a sight forlorn! - the hag lay on the ground;

E'en where she lay was turned the clay, and limb and reeking bone

Within the earth, with rabid mirth, by Ranulph grim were thrown.

And while as yet the soil was wet with that poor witch's gore,

A lime-tree stake did Ranulph take, and pierced her bosom's core;

And, strange to tell, what next befell! - that branch at once took root,

And richly fed, within its bed, strong suckers forth did shoot.

From year to year fresh boughs appear - it waxes huge in size;

And, with wild glee, this prodigy Sir Ranulph grim espies.

One day, when he, beneath that tree, reclined in joy and pride,

A branch was found upon the ground - the next, Sir Ranulph died!

And from that hour a fatal power has ruled that Wizard Tree,

To Ranulph's line a warning sign of doom and destiny:

For when a bough is found, I trow, beneath its shade to lie,

Ere suns shall rise thrice in the skies a Rookwood sure shall die!

A wretched hag her footsteps drag beneath his lordly wood,

His bloodhounds twain he called amain, and straightway gave her chase;

Was never seen in forest green, so fierce, so fleet a race!

With eyes of flame to Ranulph came each red and ruthless hound,

While mangl'd, torn - a sight forlorn! - the hag lay on the ground;

E'en where she lay was turned the clay, and limb and reeking bone

Within the earth, with rabid mirth, by Ranulph grim were thrown.

And while as yet the soil was wet with that poor witch's gore,

A lime-tree stake did Ranulph take, and pierced her bosom's core;

And, strange to tell, what next befell! - that branch at once took root,

And richly fed, within its bed, strong suckers forth did shoot.

From year to year fresh boughs appear - it waxes huge in size;

And, with wild glee, this prodigy Sir Ranulph grim espies.

One day, when he, beneath that tree, reclined in joy and pride,

A branch was found upon the ground - the next, Sir Ranulph died!

And from that hour a fatal power has ruled that Wizard Tree,

To Ranulph's line a warning sign of doom and destiny:

For when a bough is found, I trow, beneath its shade to lie,

Ere suns shall rise thrice in the skies a Rookwood sure shall die!

Friday, 24 August 2007

Buying books by William Harrison Ainsworth

If you are interested in reading on from the brief extract below, or in any other novel by this author, do not look in a new bookshop. Go instead to your local second-hand book store, where you will probably find some Ainsworth volumes at very reasonable prices. Alternatively, you could look at www.abebooks.com or www.amazon.com for on-line used bargains. It's great fun to pick up an antique volume of around 150 years old to take you back into the exciting worlds created by WHA.

Good hunting!

Steve

ps, coming soon - a poetical extract from Rookwood, Ainsworth's first novel (see earlier posting).

Good hunting!

Steve

ps, coming soon - a poetical extract from Rookwood, Ainsworth's first novel (see earlier posting).

Wednesday, 8 August 2007

The opening page of Jack Sheppard

Chapter 1

The Widow and her Child.

On the night of Friday, the 26th of November, 1703, and at the hour of eleven, the door of a miserable habitation, situated in an obscure quarter of the Borough of Southwark, known as the Old Mint, was opened;and a man, with a lantern in his hand, appeared at the threshold. This person, whose age might be about forty, was attired in a browndouble-breasted frieze coat, with very wide skirts, and a very narrow collar; a light drugget waistcoat, with pockets reaching to the knees;black plush breeches; grey worsted hose; and shoes with round toes, wooden heels, and high quarters, fastened by small silver buckles. He wore a three-cornered hat, a sandy-coloured scratch wig, and had a thick woollen wrapper folded round his throat. His clothes had evidently seen some service, and were plentifully begrimed with the dust of the workshop. Still he had a decent look, and decidedly the air of one well-to-do in the world. In stature, he was short and stumpy; in person,corpulent; and in countenance, sleek, snub-nosed, and demure.

Immediately behind this individual, came a pale, poverty-stricken woman, whose forlorn aspect contrasted strongly with his plump and comfortable physiognomy. She was dressed in a tattered black stuff gown, discolouredby various stains, and intended, it would seem, from the remnants of rusty crape with which it was here and there tricked out, to represent the garb of widowhood, and held in her arms a sleeping infant, swathed in the folds of a linsey-woolsey shawl.

Notwithstanding her emaciation, her features still retained somethingof a pleasing expression, and might have been termed beautiful, had it not been for that repulsive freshness of lip denoting the habitual dram-drinker; a freshness in her case rendered the more shocking from the almost livid hue of the rest of her complexion. She could not be more than twenty; and though want and other suffering had done the workof time, had wasted her frame, and robbed her cheek of its bloom and roundness, they had not extinguished the lustre of her eyes, nor thinned her raven hair. Checking an ominous cough, that, ever and anon, convulsed her lungs, the poor woman addressed a few parting words to her companion, who lingered at the doorway as if he had something on his mind, which he did not very well know how to communicate.

The Widow and her Child.

On the night of Friday, the 26th of November, 1703, and at the hour of eleven, the door of a miserable habitation, situated in an obscure quarter of the Borough of Southwark, known as the Old Mint, was opened;and a man, with a lantern in his hand, appeared at the threshold. This person, whose age might be about forty, was attired in a browndouble-breasted frieze coat, with very wide skirts, and a very narrow collar; a light drugget waistcoat, with pockets reaching to the knees;black plush breeches; grey worsted hose; and shoes with round toes, wooden heels, and high quarters, fastened by small silver buckles. He wore a three-cornered hat, a sandy-coloured scratch wig, and had a thick woollen wrapper folded round his throat. His clothes had evidently seen some service, and were plentifully begrimed with the dust of the workshop. Still he had a decent look, and decidedly the air of one well-to-do in the world. In stature, he was short and stumpy; in person,corpulent; and in countenance, sleek, snub-nosed, and demure.

Immediately behind this individual, came a pale, poverty-stricken woman, whose forlorn aspect contrasted strongly with his plump and comfortable physiognomy. She was dressed in a tattered black stuff gown, discolouredby various stains, and intended, it would seem, from the remnants of rusty crape with which it was here and there tricked out, to represent the garb of widowhood, and held in her arms a sleeping infant, swathed in the folds of a linsey-woolsey shawl.

Notwithstanding her emaciation, her features still retained somethingof a pleasing expression, and might have been termed beautiful, had it not been for that repulsive freshness of lip denoting the habitual dram-drinker; a freshness in her case rendered the more shocking from the almost livid hue of the rest of her complexion. She could not be more than twenty; and though want and other suffering had done the workof time, had wasted her frame, and robbed her cheek of its bloom and roundness, they had not extinguished the lustre of her eyes, nor thinned her raven hair. Checking an ominous cough, that, ever and anon, convulsed her lungs, the poor woman addressed a few parting words to her companion, who lingered at the doorway as if he had something on his mind, which he did not very well know how to communicate.

Friday, 3 August 2007

Three novels to get started

Ainsworth wrote some 40 novels during his long career, but these three were among his greatest and most popular, establishing him as one of the foremost English novelists of the 1830s and 40s:

Rookwood (1834). The first gothic novel with an English setting. Features Dick Turpin’s ride to York on Black Bess - a legend in the making!

Jack Sheppard (1840). The story of the notorious eighteenth-century criminal and Newgate escapologist, victim of the infamous Jonahan Wild. This was Ainsworth’s most successful novel, outselling Dickens at this point in his career. The book sparked off some controversy about the author’s treatment of his anti-hero, and has been described as ‘the high point of the Newgate novel as entertainment’.

Old St Paul’s (1841). A tale of the Plague and the Fire, based on published and unpublished works by Defoe.

Rookwood (1834). The first gothic novel with an English setting. Features Dick Turpin’s ride to York on Black Bess - a legend in the making!

Jack Sheppard (1840). The story of the notorious eighteenth-century criminal and Newgate escapologist, victim of the infamous Jonahan Wild. This was Ainsworth’s most successful novel, outselling Dickens at this point in his career. The book sparked off some controversy about the author’s treatment of his anti-hero, and has been described as ‘the high point of the Newgate novel as entertainment’.

Old St Paul’s (1841). A tale of the Plague and the Fire, based on published and unpublished works by Defoe.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)